Crumb (1994, Documentary): Everything bizarre is also inherently sad

Robert Crumb's life-story in a documentary that's unapologetic, funny and unorthodox - much like his own art

In one of the earlier scenes, Robert Crumb sits down with his brother Charles and tries to pull something out of him for the sake of the film. Charles is coy in the beginning, unwilling to give away much but gradually, his nonchalance grows and before we realize it, he starts talking about being on anti-depressants, about subconsciously forcing his kid brother Robert to take up sketching like he did and even inanely mentions suicidal thoughts & desolation. In another scene, a little later, Robert's younger brother Max, while on the topic of family, describes the three brothers as "primordial monkeys" to which Robert responds with "Me and Max slept in the same bed together until we were 16 or something. Very intimate, you know, close situation.". In some ways, through the garb of a documentary, Robert Crumb confronts his past casually and shows us that his genius came at the cost of being subject to a relentlessly bizarre and melancholic upbringing.

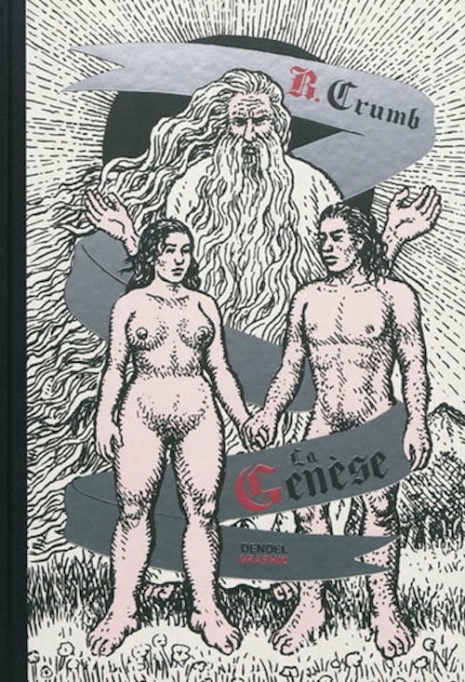

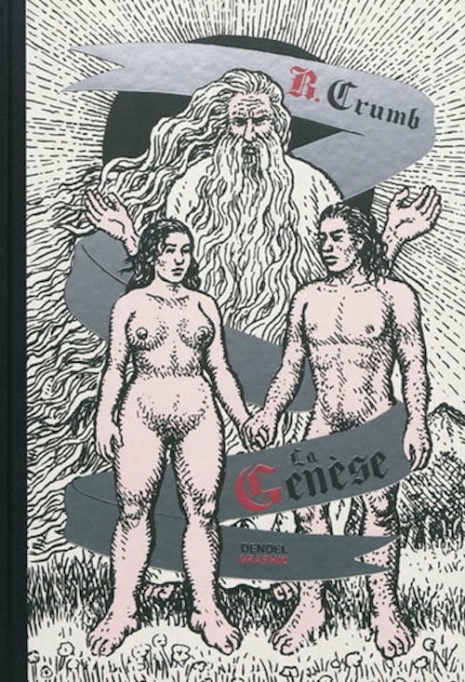

Crumb's weirdness could never be explained. A scrawny, tall man with hard-rimmed glasses on his face which mostly bore an unwarranted grin, he drew startling pornography that was incestuous, inexplicable and also very evocative - somehow, these things do not fit together very well usually but that's where his genius came through. The drawings often featured a quintessential American family of the 50s with a hardworking father, a doting mother and two kids - one boy and one girl - living a life that's so affable and inspiring that one might despise their own real family. But Crumb makes them have sex with each other. Each family member would take turns and before you realize you have uncanny imagery in front that might well have been a result of Crumb's devilish misleadings. You go through his other significant artwork and you find more strange images which upon further inspection will tell you that there is something important he's trying to tell us. Or, it could be further deception for all we know. Most of his subjects are women - young, middle-aged, old - but women nevertheless who have taken up new forms but somehow retain the core essence of their personalities - large (almost improbably gigantic) breasts in some cases and heavy-haired private parts in others - but it would be fair to say that they, apart from being figments of his unique imagination, are also significant players in the shaping of this masterful artist's psyche. A lot of Crumb's predispositions stem from how he led his life - through childhood till the time the documentary was recorded. He was an awfully shy kid, as he very honestly admits, and his interactions with people, let alone girls, might very easily have been a case-study for a psychology major. During the movie, he goes through his high-school yearbook and mentions a couple names who were his supposed interests or crushes back in the day. In a follow-up scene, he sketches them beautifully only to finally embellish them with some of his famous touches. Crumb isn't a bad-hearted person by any means and that, by design, comes through in the film (another reason why it's a masterpiece). Instead, his art is a sanctuary to him, where he is allowed to openly admit his wild thoughts and create impressions of his mind that won't be mocked at. The women in his art, for example, some times have beaks like mystical birds from Greek folk literature and some times they have incredibly heavyset hairy bodies with gaits of mean-minded creatures who are out to destroy you. But, somehow, it all ends in sex.

Crumb was often accused of being sexist, by blatantly objectifying the women in his sketches. But, owing to vast collection of art, it'll take proper scrutiny to fathom the whys and hows of this.

That isn't to say that Crumb drew just porn. There are strong sexual motifs in his work, no doubt, but only as expressions of a repressed sexual development that he may have endured while growing up. Terry Zwigoff, the director of the film, starts off on this note but quickly introduces us to the stark change that Crumb encountered later in his adult life - a parade of lovers are introduced who gush about him, hold him in great regard and genuinely love him for who he really is. Crumb, perhaps, - and this being my own imagination about the whole deal - might not have known how to deal with all the attention because in complete contrast to how his life fared, his two brothers ended up as complete misfits who failed to get much recognition. Charles, his older brother, is credited in many places as the inspiration to his art and also appears as a character in many of Crumb's comics. Charles' life is peculiar and his own sexual muddles that lasted almost all his life may have influenced his kid brother Robert to think of sex as something funny and grotesque at the same time. Robert Crumb studied sex in his own way much like Alfred Kinsey did, except that Crumb found curiosity in the perverseness of it.

The documentary, unlike most films, is an ode to not the person or the artist but the life he has led. Sure, the life made the artist but you replace him in his own story with any other person, it'll still come off bloody interesting. A rare quality to cinema where we cringe every moment and yet celebrate art as though we are patrons of its aesthetics and not the deep trauma it carries. And by trauma I mean a slow-simmering type of ambiguity and sadness that leads to either mental breakdown or hangs on to thin threads to turn you into an art maverick. Terry Zwigoff, apparently, hung on to a thin thread himself before and during the making this film. It took a threat on his part when he (and this being a legend, mind you) told Robert Crumb that if the documentary didn't get made, he would shoot himself. Years later, this story still resonates with those who could and couldn't make it because that's exactly what Robert Crumb did.

Fuzzy the Bunny - an anthropomorphic animal character that Charles Crumb is credited with as the co-creator. Most of Charles' cartooning was based on 50s Disney characters with a huge fan-fiction element to it.

The documentary, unlike most films, is an ode to not the person or the artist but the life he has led. Sure, the life made the artist but you replace him in his own story with any other person, it'll still come off bloody interesting. A rare quality to cinema where we cringe every moment and yet celebrate art as though we are patrons of its aesthetics and not the deep trauma it carries. And by trauma I mean a slow-simmering type of ambiguity and sadness that leads to either mental breakdown or hangs on to thin threads to turn you into an art maverick. Terry Zwigoff, apparently, hung on to a thin thread himself before and during the making this film. It took a threat on his part when he (and this being a legend, mind you) told Robert Crumb that if the documentary didn't get made, he would shoot himself. Years later, this story still resonates with those who could and couldn't make it because that's exactly what Robert Crumb did.

Comments

Post a Comment